Ventricular and Atrial Hypertrophy and Dilation

Ventricular and Atrial Hypertrophy

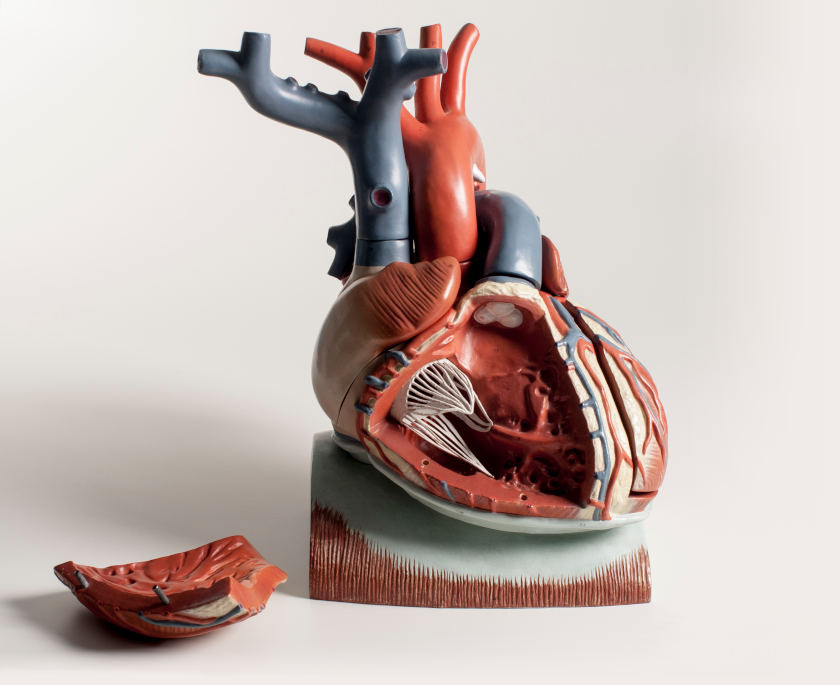

An increase in the size and mass of the ventricle is referred to as ventricular hypertrophy. This can be a normal response to cardiovascular conditioning, as it occurs in athletes. This physiological hypertrophy enables the heart to pump more effectively and is reversible. In contrast, other forms of hypertrophy are caused by ventricular remodeling in response to increased stress, such as increased pressure load (afterload). Prolonged stress-induced hypertrophy can lead to ventricular failure. Hypertrophy can also result from diseases of the heart, such as valve disease and cardiomyopathies, genetic abnormalities (e.g., hypertrophic cardiomyopathy), and ischemic heart disease (coronary artery disease).

With chronic pressure overload, as occurs with chronic hypertension or aortic valve stenosis, the ventricular chamber radius may not change; however, the wall thickness increases as new sarcomeres are added in-parallel to existing sarcomeres. This is termed concentric hypertrophy. The thicker ventricle can generate greater forces and higher pressures, while the increased wall thickness maintains normal wall stress. This type of ventricle becomes "stiff" (i.e., compliance is reduced), which can impair filling and lead to diastolic dysfunction. Sometimes the chamber diameter is increased and the wall thickness is increased moderately. This is termed eccentric hypertrophy, and can occur when there is both volume and pressure overload.

Atria, like the ventricles, can undergo hypertrophy in response to increased afterload. For example, mitral valve stenosis increases resistance to blood flow across the valve, which requires higher pressures in the left atrium to drive ventricular filling. This pressure afterload stimulates the wall of the left atrium to thicken.

Ventricular and Atrial Dilation

Chronic ventricular dilation occurs in response to:

- Chronic volume overload stimulated by elevated ventricular end-diastolic pressures (e.g., as occurs in aortic and mitral regurgitation; systolic dysfunction)

- Hypervolemic states triggered by ventricular failure or renal failure

- Intrinsic disease, such as idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy or known causes of dilated cardiomyopathy (e.g., alcohol or viral induced cardiomyopathies)

Ventricular dilation occurs as new sarcomeres are added in-series to existing sarcomeres. Mechanically, dilation increases the ventricular compliance. The dilated ventricle has elevated wall stress and oxygen demand, and lower mechanical efficiency. Clinically, it is commonly associated with symptoms of heart failure and reduced ejection fraction.

The atria can also undergo dilation in response to chronic volume overload. For example, in mitral valve regurgitation, the volume and pressure of the left atrium are greatly increased. The left atrium responds by undergoing chronic dilation, which enables it to accommodate the increased volume without as large an increase in pressure because of its increased compliance.

Hypertrophy and dilation are examples of cardiac remodeling. Under some conditions (e.g., exercise training) remodeling is beneficial; however, under other conditions (e.g., heart failure) remodeling is deleterious because it increases the oxygen demand of the heart and decreases mechanical efficiency. Certain drugs, such as beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers have been shown to prevent or partially reverse remodeling under pathologic conditions.

Revised 01/29/2023

Cardiovascular Physiology Concepts, 3rd edition textbook, Published by Wolters Kluwer (2021)

Cardiovascular Physiology Concepts, 3rd edition textbook, Published by Wolters Kluwer (2021) Normal and Abnormal Blood Pressure, published by Richard E. Klabunde (2013)

Normal and Abnormal Blood Pressure, published by Richard E. Klabunde (2013)